From being arrested age 20 to becoming the infectious diseases expert leading Jersey's pandemic response, Express got to know the man behind the science.

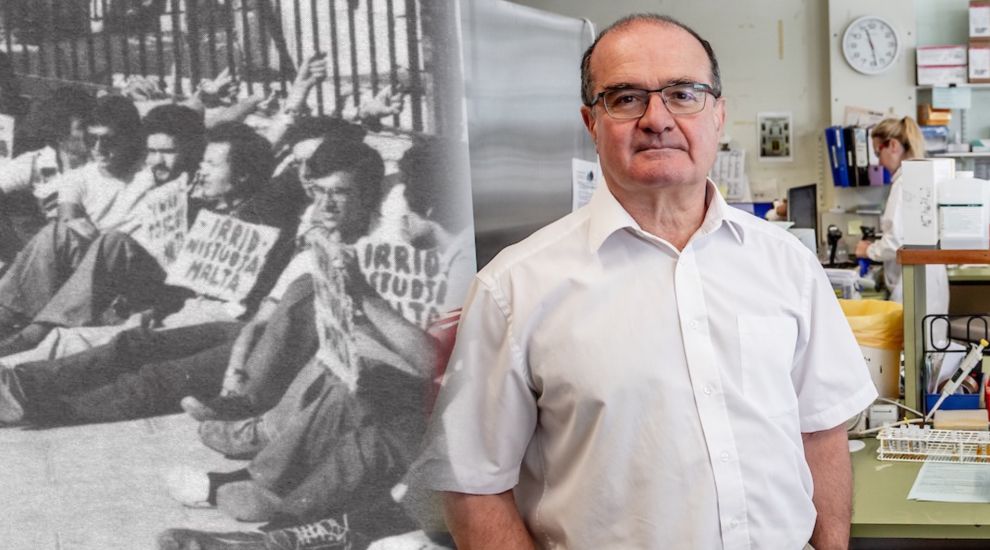

At 20 years old, Ivan Muscat was arrested.

Alongside his fellow junior doctors carrying ‘I want to study in Malta’ plaques, the Maltese rebel with a cause chained himself to the railings of the Prime Minister’s office.

Amid a dispute with government, his medical school had been closed and the students desperately wanted to return.

“Good grief! You managed to unearth that?” Dr Muscat, now the man leading Jersey’s covid response, laughs as he delves into the memory.

“It was a peaceful expression of our strong feeling that the medical school should open. The police cut our chains and took us away in a bus to the main police headquarters and our parents came and collected us.

“It was important to make the point. After that symbol of our feelings, we did have a long meeting with the government in the Prime Minister’s office, but the medical school didn’t reopen.”

It was an early rehearsal of speaking truth to power for a man who would later become accustomed to it, and the trigger for a move that would eventually bring him to Jersey, where he is now leading the response to the covid pandemic.

After the protest in Malta failed (and the railings eventually removed from the building), the British Medical Association stepped in to help Dr Muscat and his colleagues find places in medical schools across England.

Pictured: Dr Muscat's discussions with Malta's Prime Minister were an early rehearsal of speaking truth to power.

He completed his studies in Newcastle, before jumping to Edinburgh and onto Exeter.

It was in these locations that he zoned in on his specialist areas of interest –microbiology and infectious diseases, which he loved because they allowed him to “retain patient contact but also had a scientific element and also a public health element.”

In 1989, that passion took him to Jersey, where he first arrived for some locum work on Liberation Day – “it’s a day not celebrated in the UK so I was surprised by it” – before taking on a permanent role in October.

“It was a memorable day, the first day of my career as a permanent consultant. It’s sort of a landmark.”

HIV/AIDS was the focus of the time, with the previous decade dominated by treatment difficulties.

But the mood was starting to brighten as Dr Muscat arrived in Jersey.

Pictured: Ivan Muscat fondly recalls arriving in Jersey on Liberation Day in the 1980s.

“It was actually wonderful to come in at that time when something could finally be done,” he reflected, musing on the “rewarding” nature of helping the small numbers of patients in Jersey with the drugs that started to become available in the years that followed.

“The treatments continued to improve and change and now we have largely side effect-free medication… Often with one tablet a day only, you can rapidly make someone virus-undetectable. As long as the virus is undetectable on treatment for six months or more, they are not infectious to other people at all.

“That has revolutionised the way HIV-positive people see themselves and are seen by others. That has made a big difference.”

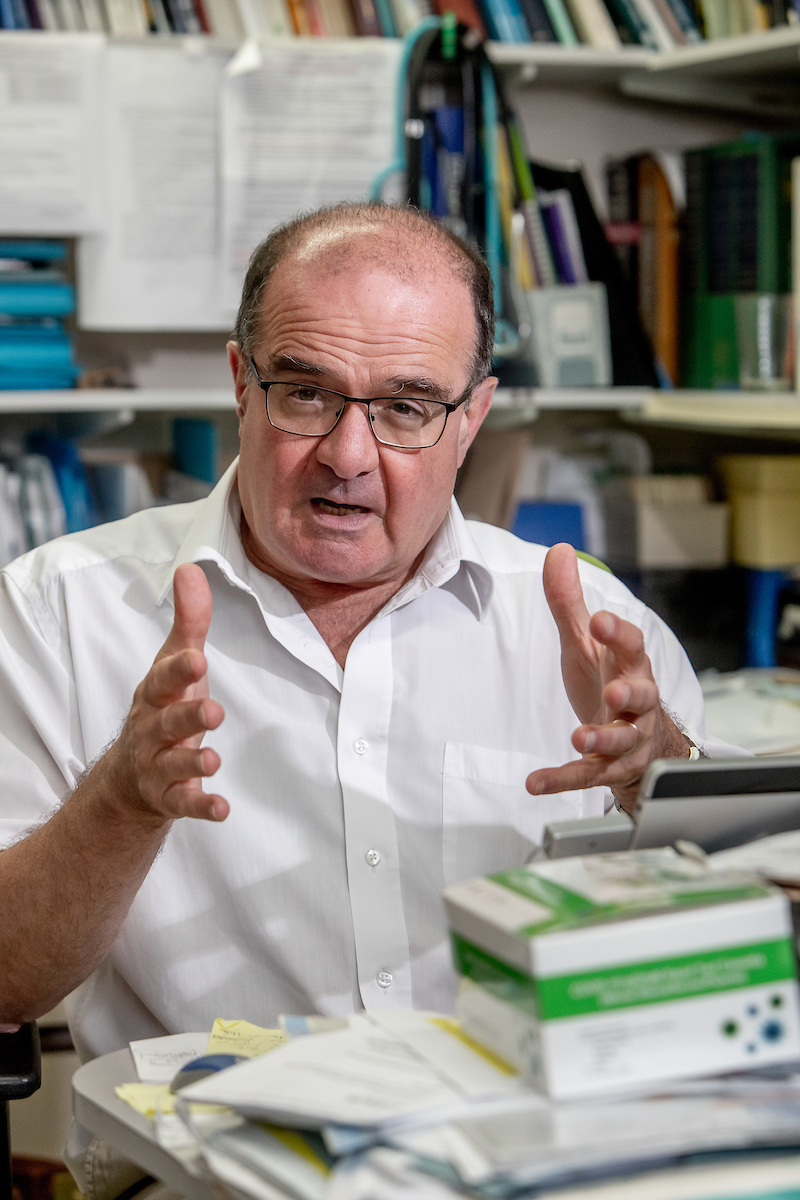

According to colleagues past and present, one of Dr Muscat’s great strengths is his personal touch.

When there was no system of support for Jersey’s first cluster of HIV patients locally, Dr Muscat offered his home contact details to help.

Pictured: According to colleagues past and present, one of Dr Muscat’s great strengths is his personal touch.

He describes personal contact with patients as “vital”.

“You are not just talking about facts on a bland piece of paper or a computer screen. You can actually see what those facts mean to an individual and therefore you take an even greater interest in the facts because you know how important they are to apply properly to individuals.

"That’s what brings the whole subject to life: the people, the patients.”

Dr Muscat’s role also saw him take control of dealing with outbreaks of MRSA and C. Difficile among others at Jersey Hospital over the years.

Pictured: The Swine Flu outbreak in 2009 was Dr Muscat's first major test.

Without realising at the time, this “bread and butter” work would set him up for making decisions in the midst of a pandemic that would affect the lives and livelihoods of more than 100,000 islanders.

“Dealing with those infections on a day-to-day basis, you start thinking about not just infection in the context of one individual, but in the context of all around. That’s the only way you can sensibly think about infection - you must think about all ramifications.”

The Swine Flu outbreak was his first major test.

The “long-feared outbreak” – as it was referred to in local headlines at the time – finally arrived in November 2009.

But, within a short period, Dr Muscat had successfully led a mission to “switch it off”.

“The key was not just vaccinating healthcare workers and those at risk, but schoolchildren. As soon as we vaccinated schoolchildren, the whole outbreak in Jersey came to a halt because schoolchildren in Jersey happen to be superspreaders of influenza.”

So impressed were global authorities by the response, that the island was invited to present at The Hague.

But then came covid, euphemistically branded a “novel challenge” by Dr Muscat, as it “behaved differently” to any illness seen before.

Pictured: Dr Muscat's next challenge came earlier this year, as covid began spreading across the world.

“There are no drugs, no therapeutic agents because it’s so completely new… Seeing the effect it had on similar countries and health services [in Europe], it was clear it was going to have a similar effect in Jersey and that of course was a worry.”

Having caught wind of the Wuhan-born infection, Dr Muscat started meeting weekly with a cross-government review group and issued early advice emphasising good hygiene and distancing from anyone that recently travelled to an affected region.

Covid moved rapidly across Europe, hitting Jersey in March. Dr Muscat announced shortly after that schools were to close. By the end of the month, the island was in lockdown.

It was a whirlwind – and one Dr Muscat found himself forced to navigate as the Acting Medical Officer for Health, as the incumbent, Dr Susan Turnbull, was on sickness leave.

Pictured: Dr Ivan Muscat explaining the island's predicted infection curve at a press conference in the early stages of the pandemic.

The days were long – 12 hours-plus, with calls sometimes following him home, and weekends packed too.

“[I was] worried, of course, because you want to get it right for all concerned. All you can do is work hard to try to get it as right as possible knowing that a perfect answer was never going to be available and it was always going to be a balance of risks.”

But, in the face of pressure, Dr Muscat was unwavering.

“If you get unduly anxious about any subject, then you may make mistakes so it’s important to just look at the facts and view them as clinically as possible.”

A good dose of laughter – the best medicine – helped, Dr Muscat admits.

Pictured: On dealing with the pandemic, Dr Muscat admits that a good dose of laughter – the best medicine – helped.

The walls of his office are adorned with cheeky cartoons, including a suitably funky ‘retrovirus’ feat. sunglasses and a handlebar moustache.

There’s even a plaque on his wall, stating, ‘P*ss off, I’m busy.’

But they pale in comparison to the scores of records, journals and research print-outs surrounding him – testament to his years of arduous work.

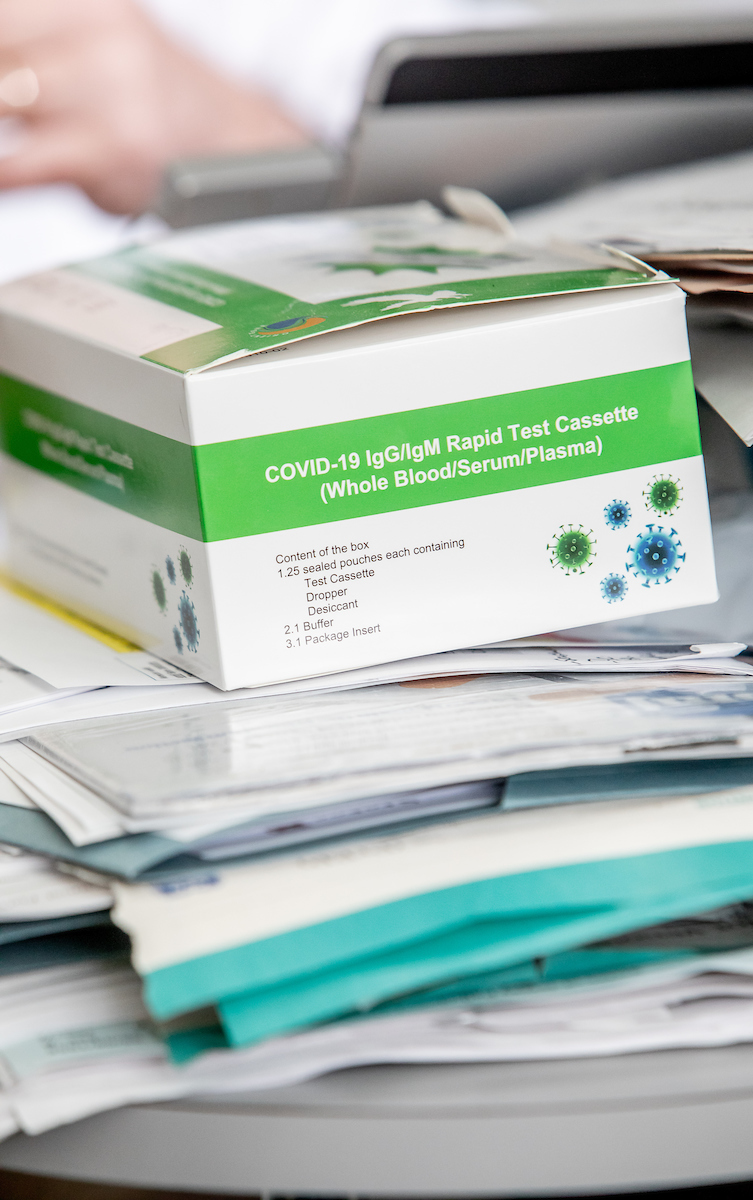

Atop a paper mountain, there’s a covid test on his desk too – a key area of focus at the moment.

Pictured: Dr Muscat's office walls feature cheeky cartoons and plaques.

At the time of the interview, Dr Muscat says he is “pushing” to bring a self-contained lab to Jersey - allowing for up to 2,000 tests to be processed a day - in anticipation of a potential second wave of cases in the winter.

Using ramped-up screening among new arrivals and in the health workforce to “switch off hidden infection before it becomes apparent is the way forward”, he explains.

Could another lockdown be on the cards? Maybe.

However, Dr Muscat says, with the right management, we should hopefully be able to avoid this.

Pictured: Dr Muscat outside the new self-contained testing lab, which can process covid tests in around just 12 hours.

The original lockdown decision was “difficult”, but a “proportionate” one taken on consideration of the “balance of risks”.

“If covid is left to its own devices, it will not only cause direct damage, but indirect damage as well because people would not be able to operate businesses or undertake normal activity because people are sick or afraid of going out… The choice we had was to either let covid impose on us not only its own damage, but secondary damage, or introduce mitigation to at least only suffer on one front and not suffer the direct effects of covid.”

As well as continuing to advise all islanders to practice good respiratory and restroom hygiene, and encouraging those with underlying illnesses or risk factors like obesity to take proactive steps to manage them, getting as many children and over-65s as possible vaccinated against flu will be a key weapon in the armoury this winter to avoid the hospital buckling under a combined spike in regular flu and covid cases.

Meanwhile, Dr Muscat is keeping an eye on international research into antibodies and vaccines.

The issue, he says, is that it’s not yet 100% clear if the presence of antibodies means someone has immunity. Even if they do, this may only be temporary.

This poses a problem for the concept of “immunity passports” – something he says “have been discussed since virtually the beginning of covid”.

Pictured: He says that Jersey's size has been a "prime asset" in managing the crisis.

“As a concept, it hasn’t gone away, but the current thinking is if you are going to go down that route you need to do a blood test on the individual every one or two months to see if antibodies are still present. It’s almost like renewing your actual passport.”

Reflecting on the management of the crisis, he says that the size of Jersey has been a “prime asset”.

“One of the major things about infection is that it is all about communication of information and Jersey lends itself very easily to that. There is one microbiology lab, one hospital in a circumscribed island so all the infection-related information and ‘gossip’ so to speak all comes through Microbiology and Infection Control and it’s easy then to synthesise all that information and come up with a real-time response.”

He later adds: “The beauty of working in this hospital… is you have half-a-dozen meetings by the time you walk from the car park to your office and that’s a lot of communication happening very informally and that’s a beautiful thing to live with because you get to know people well - so well that all you need is an informal chat and whatever you need is dealt with.”

This, Dr Muscat says, is “a perfect example of a panopticon approach to infection.”

Pictured: Dr Muscat says we should "enjoy the summer whilst we can" but remember that covid is "very much there in the background".

“I would very much like to continue to promote that way of thinking for the future of infection in Jersey. The approach comes naturally, and it pays dividends.”

Overall, Dr Muscat radiates a feeling of gentle optimism for the future.

“Summer does not catalyse the effects of respiratory viruses so we should take this opportunity to catch our breath and enjoy summer.”

But, ever the wise adviser, he adds the caveat: “Covid has not gone away - it’s very much there in the background and we must enjoy the summer whilst we can, but do so responsibly so we don’t have to dial back up the mitigation factors.”

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.