After long expressing support for the development of an offshore wind farm in Jersey’s territorial waters, Environment Minister Jonathan Renouf has officially announced the Government's intention to make it happen.

Yesterday, Deputy Renouf took the first formal step: lodging a proposition seeking a democratic mandate to proceed. It will be debated by States Members in May after a period of public consultation.

It is arguably the most ambitious project ever undertaken by a Jersey government, requiring billions of pounds of private investment, negotiations with giant multinationals, a huge amount of technical detail, complicated financial arrangements, a level of risk, and long-term commitments that cannot be swayed by the changing winds of the electoral cycle.

Pictured: Environment Minister Jonathan Renouf lodged a proposition seeking a democratic mandate to proceed with the wind farm plans yesterday.

It might seem a little overwhelming for a jurisdiction of 100,000 people with 45 square miles of land and 800 square miles of sea.

But Environment Minister Jonathan Renouf, backed by the Council of Ministers, is confident that Jersey can get it right, and all islanders will benefit from clean energy.

There are many stages to complete and obstacles to negotiate but, a day after the announcement, Express endeavours to provide some of the context...

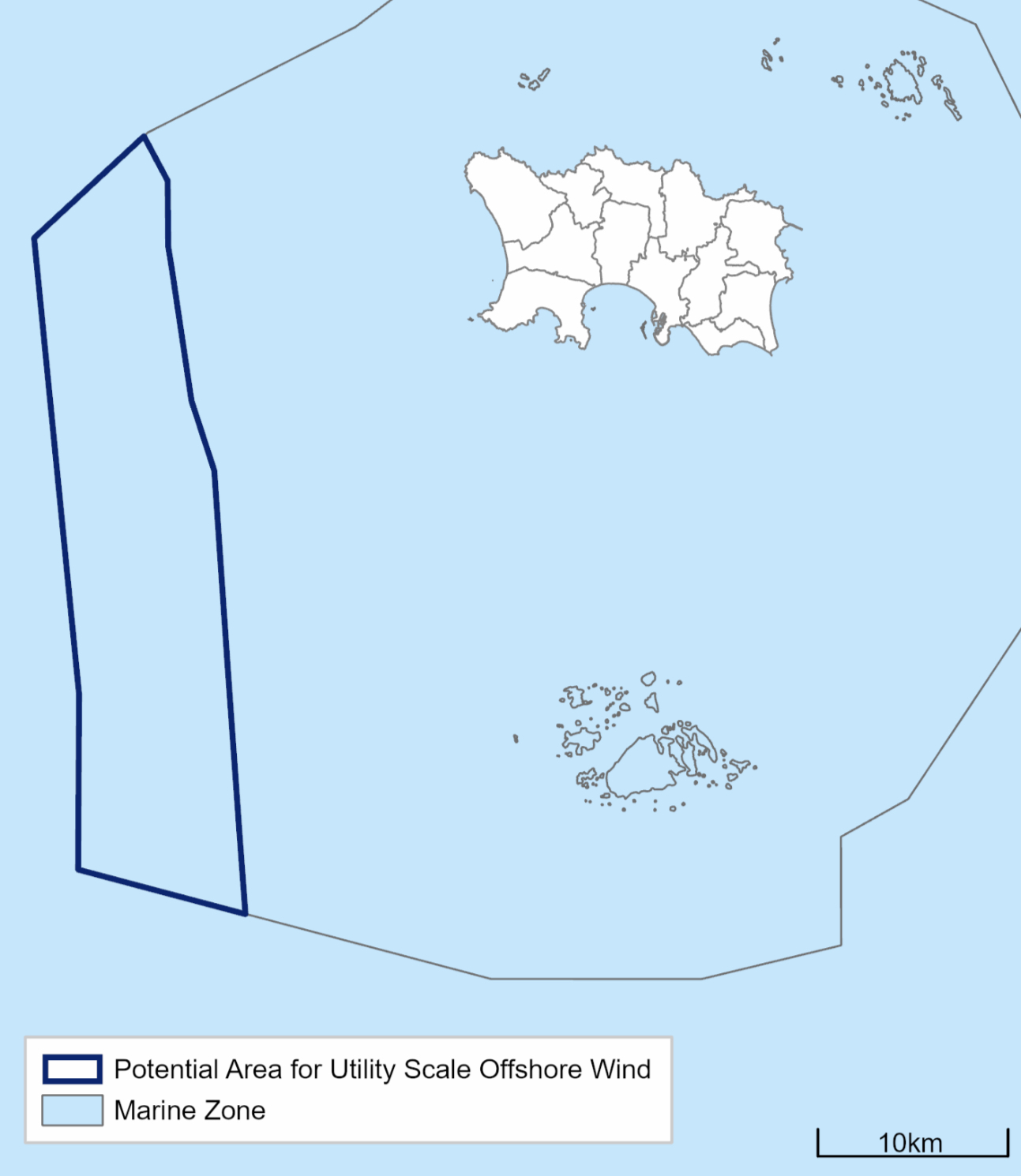

The Government believes it is right to promote and support the development of up to one gigawatt of generating capacity, in the south-west of Jersey’s territorial waters.

Generating capacity at this scale is expected to produce around 3,800 gigawatt hours of energy when wind intermittency and transmission losses are taken into consideration. That’s a utilisation rate of 43%.

Pictured: Jersey's proposed wind farm could generate twice as much power as the 62-turbine wind farm currently being built north of Saint Brieuc, which comes very close to Jersey’s territorial waters.

This is around six times Jersey’s current electricity demand, and around twice the requirement if all the energy needs of the current economy – including transport and home heating – were powered entirely by electricity.

By contrast, the offshore wind farm currently being built for the French market to the south west, is a 496 MW facility, so Jersey’s will be twice as powerful.

Islanders need only look out from Corbière on a clear day to see that a wind farm in the Bay of Mont Saint Michel is a real and viable prospect. Even a visit to the Harbour over the last year or so would provide evidence, as Jersey remains a regular stop-off for boats working on the Saint Brieuc farm.

The French project is likely to be a useful template for the Government – not only will it hope to leverage off some of the work that was done to get the 62-turbine farm up and running, including key environment impact assessments, but it could also help define the technical and business models.

Also, from a visual point of view, Deputy Renouf has said that, from most viewpoints, Jersey’s windfarm will appear as an extension of the French installation.

The wind farm is being built by a consortium led by Spanish energy giant Iberdrola, which in 2020 took full control of a company called Ailes Marines, which is developing, constructing and operating the project, 16 km off the Brittany coast in a 75 sq km area of sea.

Pictured: The construction of the French wind farm is clearly visible from Jersey.

The journey to consent was not easy, and the project only got the green light in 2019 after the Conseil d’Etat, France’s supreme administrative court, rejected appeals against a Saint Brieuc ruling that criticism regarding the legality of Ailes Marines’ operating licence was unfounded.

The expected energy production will amount to 1,850 gigawatt hours, equivalent to the electricity consumption of 835,000 inhabitants, or 9% of Brittany’s total electricity consumption.

The 62 wind turbines are arranged in seven lines of three to 14 turbines, spaced at approximately 1,300m apart. An electrical substation is located in the centre of the wind farm, aligned with the turbines in the fourth row.

The substation transforms the energy produced by the machines and transfers it to the French mainland via two 225,000-volt cables.

Where these cables land from Jersey’s wind farm is yet to be decided but it is likely to require a substantial area of land. In France, the connection into the grid near the port of Erquy is being managed by state-owned utility RTE, the French grid owner and operator.

In Jersey, that role is carried out by the state-majority-owned JEC, who have previously shared their enthusiasm to be involved in any consortium.

Ministers are proposing that the development of offshore wind should be privately funded and designed and delivered by a consortium with experience of similar development elsewhere.

They say that this approach is the most likely to deliver a viable scheme that is progressed to internationally recognised standards.

However, they add that any opportunity for either the public of Jersey or the Government to invest directly in the scheme will be kept under review and would be “subject to detailed appraisal and, in the case of government investment, would be subject to appropriate consideration by the States Assembly”.

However, clearly Government time and resource will be used to create the policy and legal frameworks to consent development, and to regulate the operations.

So far, work on the project has been met from within existing budgets; however, the next Government Plan allocates £500,000 from the Climate Emergency Fund to fund wind farm costs next year.

Longer term, if Jersey’s preferred model was adopted, a successful consortium would lease the seabed from the Government, which has owned it since 2015, when it was transferred from the Crown.

The Government hope to run an initial competitive tender process in 2025 to secure an option for lease, which is usually based on a financial value offered for the development site option and a price per unit for energy that would subsequently be generated. At this stage, payments would reserved, and the purchaser retains the option not to lease the site.

Getting the right price at which the Government would buy the electricity is key. Recently, the UK’s climate ambitions suffered a blow after no new offshore windfarms were secured in Westminster’s latest clean energy auction, despite there being the potential for five gigawatts of projects – five times Jersey’s ambitions.

Pictured: A suitable area for a wind farm is identified in the Bridging Island Plan.

Offshore wind developers had warned that the auction’s maximum price, which was similar to previous auction rounds, was now too low for their projects to make any money.

If Jersey names the price right and a consortium is selected, the two sides would then sign a ‘lease purchase contract’, which is put in place once the development consents, supply chain, power purchase agreement and investments are finalised.

This stage can unlock payment for the rights to the site, but any leasing payments attributable to the energy that is generated are usually deferred until the wind farm is operational.

Global companies in the wind farm game include Danish multinationals Ørsted and Vestas, UK firm SSE Renewables, Italian corporation Enel Green Power and Spanish firms EDP Renewables and Iberdrola. French state-owned electricity provider EDF also builds wind farms, including in the UK.

Once a development consortium has secured the option for lease, they would then begin the extensive and detailed work necessary to seek a full development consent that extends to construction, operation and decommissioning.

According to the Government, this work will include steps to:

At this point, an application for consent would be submitted, which would be assessed against a specific consenting law which the Council of Ministers will bring to the Assembly for debate next year.

Following an award of consent, a lease purchase contract would be put in place, following which, subject to meeting any pre-commencement conditions, the construction phase can begin. The Government hope this will be from 2026.

The wind is, by nature, intermittent so there are no plans to exclusively rely on it to meet the island's power needs. How reducing the amount of power Jersey imports from France will impact on the island's purchasing power will no doubt be a key discussion point.

The Saint Brieuc wind farm, which should be fully commissioned by the end of this year, is estimated to have cost 2.4 billion euros, or around £2 billion.

A budget for the Jersey wind farm is yet to be finalised but the cost is likely to be billions. Although the money will come from private investment, Jersey will clearly still be hoping that inflation remains low while the cost of such items as jackets, turbines, blades, cables and transformers come down, at least in relative terms, as the market matures and technology advances.

Now that the Government has announced its intent, there will now be a ‘public engagement phase’ during which islanders will have a chance to understand more about the proposals and have their say. This will cover a 14-week period from early next month to early February.

An ‘industry engagement phase’ will take place from mid next month, in which Government will hold a structured series of ‘without prejudice’ conversations with potential developers, power purchasers, project advisors and investors.

These phases will then feed into the key in-principle States debate next March.

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.