For most people crossing Westminster Bridge on their regular trips in and out of London, the surroundings probably soon cease to be particularly noteworthy... but not for one young islander.

No matter how many times David Houiellebecq's mother took him across the bridge to meet his father when he finished work in the City, there was one landmark which not only never lost its wonder but which also inspired his career choice of repairing and restoring timepieces.

Express went to meet him...

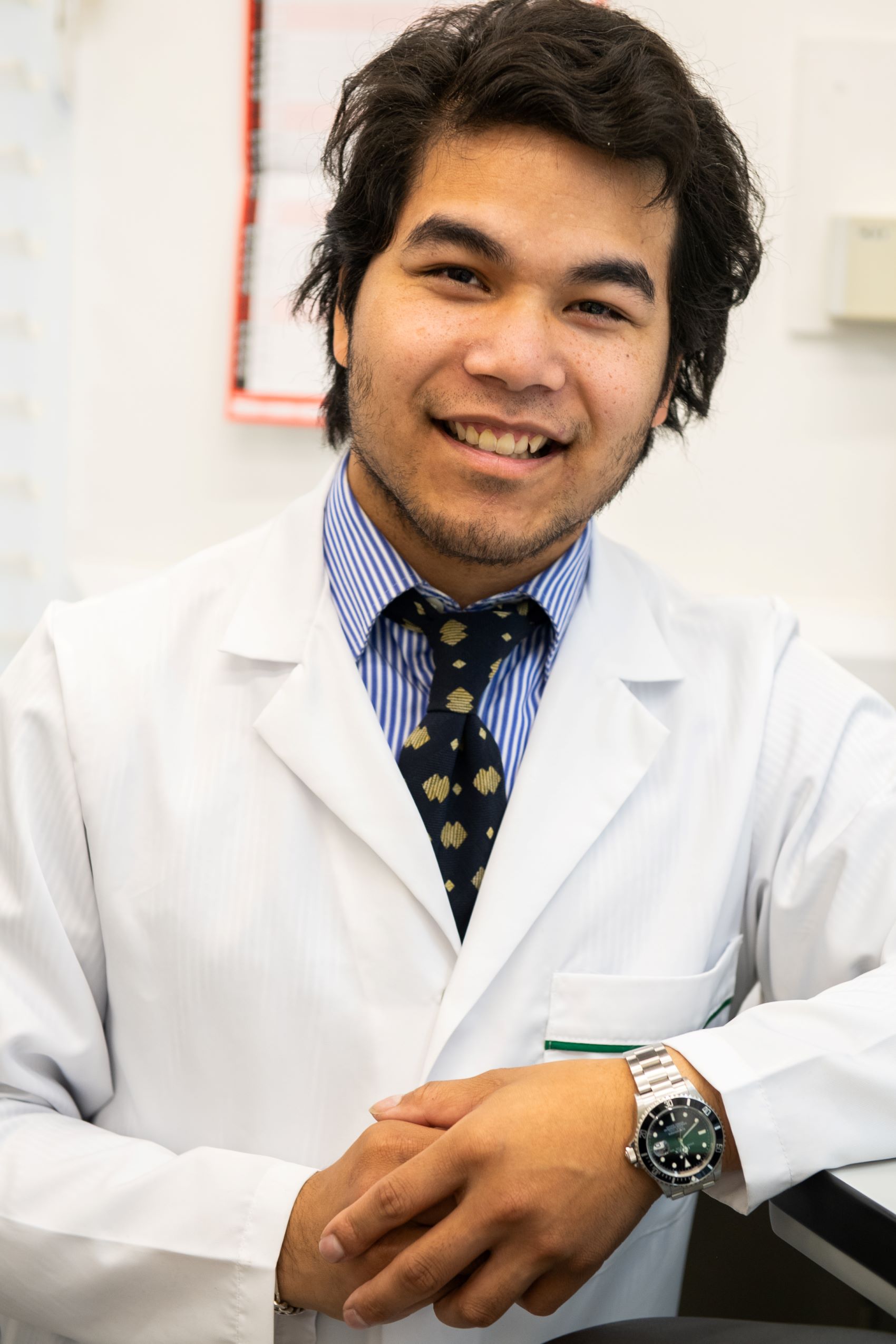

“I was always fascinated by Big Ben and, from the age of three, I wondered what went on behind the scenes and how it worked,” smiled the Hettich watchmaker.

It was a fascination which went on – much to the occasional frustration of his parents – to dominate David’s childhood.

“When I was five years old, I took apart the bedside alarm clock to see how it worked,” he recalled.

“Unfortunately, though, I couldn’t put it back together again, which got me into some trouble.”

Despite that blip, David continued developing his mechanical knowledge and his love of all things horological during his school years.

“At secondary school, you were often asked where you saw yourself in five years’ time,” reflected the former St Peter’s School and Les Quennevais student.

“While a lot of my contemporaries had no idea what they wanted to do, I always knew that I wanted to work with watches and clocks.”

So focused was David on that career path that, when the opportunity arose to undertake three weeks’ work experience as part of Project Trident, there was no doubt in his mind about where he wanted to spend that time.

Pictured: By the age of 18, David had a collection of more than 200 clocks.

“I spent those three weeks at Hettich, in this very room, sitting alongside my now colleague Stuart McCourt,” he said, looking around the workshop above the King Street jewellery showroom.

Being introduced to the team at Hettich and having the chance to “work on a couple of Swiss movements” only strengthened David’s enthusiasm to enter the profession – although it was an ambition which took slightly longer to come to fruition than he had first hoped.

“When I left Les Quennevais, I had already agreed with Hettich that I was going to study watchmaking and join the firm,” he explained. “Unfortunately, though, I couldn’t enrol on the course until I was 18, which was really frustrating.”

Channelling that frustration in a positive way, David completed a two-year art and design course at Highlands College before joining Hettich as an apprentice watchmaker.

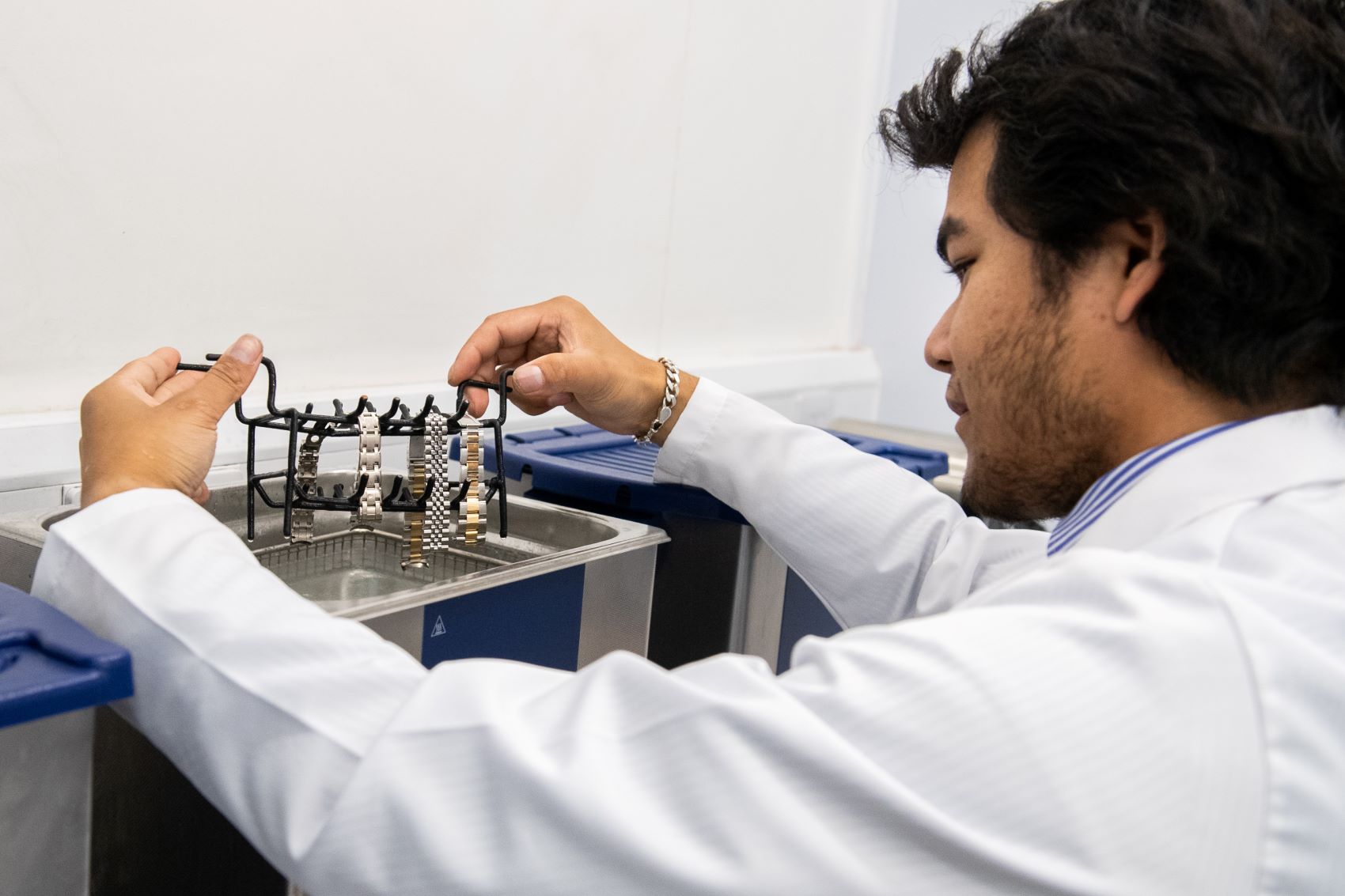

Pictured: Watch bracelets being lowered into the ultrasonic cleaning bath (Rob Currie).

“I spent three months getting to know the business and my colleagues while gaining an understanding of how the fine-watch-making world works and getting some training at the bench from Stuart,” he said.

“Then, in January 2019, I headed to Manchester to undertake the Watches of Switzerland Training and Education Programme.”

But, as he took his place for the first few days of the one-year – or 1,300-hour course – David admits to being somewhat surprised by the programme’s content.

“The whole idea of the course is to take someone with no knowledge about watches and turn them into a fully qualified watch technician, so it was pretty intense,” he admitted.

Pictured: The tools of the trade. (Rob Currie)

“Despite that, for the first two months, we didn’t touch a single watch. Instead, we were filing and sanding brass into squares and cubes, the idea being that this would test our dexterity and precision and help us to meet very, very fine tolerances. It wasn’t what I was expecting, but it definitely gave me the skills to progress.”

As the students began blending practical and theoretical work, they studied the reference book The Theory of Horology, as well as beginning to work on basic manual-wind watches.

“Interestingly, when you look at both the theory and the practices involved with fine watchmaking, you realise that, although some of the techniques and materials have changed over the years, the basic principles remain the same,” he said.

After passing an exam in which he was required to strip, diagnose the faults with and service a mechanical watch, David was able to move on to battery- and circuit-based quartz watches before the “more complicated” work started.

“A complication in a watch is effectively any functional feature within the timepiece,” he explained. “For example, if a watch also has features such as the date, moon phase and/or a stopwatch, it would be classified as a complicated watch.”

Despite the name, though, David says that “complicated watches” are not always the hardest pieces to repair.

“Watches that have been looked after, and are in a generally good condition, are usually easier to work with than, say, a timepiece which has suffered water damage,” he said. “Therefore, a basic watch in poor condition could be more challenging to repair than a complicated watch in a good condition.”

The most challenging job in any timepiece, he says, is replacing a balance staff.

Pictured: "A basic watch in poor condition could be more challenging to repair than a complicated watch in a good condition.” (Rob Currie)

“That is effectively the beating heart of the watch,” David explained. “The balance wheel regulates the piece’s timekeeping, while the staff is the very delicate component in which the wheel pivots. The process of replacing the balance staff is hugely intricate, as the balance wheel has to be perfectly poised, otherwise you will have timekeeping issues. That’s where the real science of watchmaking and repairs comes in.”

As well as completing the course in Manchester, which he says “allows him to work professionally at the bench and opens the door to further training with specific brands”, David has undergone his Rolex Level 30 and Patek Philippe essential maintenance qualifications.

“We stock Tag Heuer, Omega, Breitling, Tudor, Rolex, Patek Philippe, Chopard, Cartier and Mont Blanc watches at Hettich and offer different levels of maintenance services for each brand,” he said. “For example, we carry out full servicing on Rolex whereas, with Patek Philippe, we only undertake minor interventions such as strap replacements.”

And it is these two brands, which the 23-year-old describes as “la crème de le crème” of watches, for which he says they see the most demand.

“These are not just day-to-day watches but also real collector’s items and each watch tells a story,” he said.

Pictured: David taking a watch apart for servicing. (Rob Currie)

“Whether it is a birthday present, a graduation gift or a retirement present, or perhaps a piece which has been handed down through the generations of a family, every watch has a different story.

“It’s always interesting to see the different types of watches which come into the workshop and to know that each one has such a personal connection to someone. We see everything from vintage watches from the 1960s through to modern designs.”

While appreciating both the stories and the workmanship behind each watch, David admits that his choice of career is “quite unusual for young people” although he says that more youngsters are now taking an interest in timepieces.

“When I look at my contemporaries at school, a lot of them were interested in mechanics but most of them went on to apply this in the motor trade,” he said. “While a lot of people are interested in watches, few choose to make a career out of servicing and repairing these items. However, if you are considering doing something a little bit different and are interested in a career with is creative, mechanical and hugely satisfying, then watchmaking is definitely something to think about.”

And with a growing interest in watches comes, says David, a burgeoning new hobby.

“The idea of having a watch collection is something which has only really come about in the past 20 years or so,” he said. “While the tradition of giving fine watches for special occasions remains, there is now a growing number of people who like collecting watches because they are interested in the art, brands and history of each piece.

“Watches also make great investments, as not only do they retain their value, but they are beautiful items to hand down to future generations.”

With David now fulfilling his own professional dreams, he is keen to encourage more people to follow in his footsteps.

“Anyone considering a hands-on and mechanical career could think about watchmaking,” he said. “It’s a very focused and fascinating role, great for problem-solving and, in some cases, very relaxing. It’s also good for patience and concentration. In fact, I would say that patience is probably the main skill that you need.”

And it is a skill which David seems to have in abundance, with the young watchmaker admitting: “I like a challenge. The more challenging a repair or service is, the more I develop my knowledge and skills. I love it.

“Waking up each morning, knowing that I will spend the day working on fine watches, is a dream come true. In fact, it doesn’t really like a job, as I’m doing exactly what I always wanted to do.”

This article first appeared in the December 2023/January 2024 edition of Connect Magazine – read the digital version below...

Pictured top: watchmaker David Houiellebecq putting a watch bracelet back on. (Rob Currie)

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.