The bombing which occurred on the evening of Friday 28 June 1940 was a terrible and traumatic event for the Channel Islands – but it could have been far worse if a series of events had not happened 84 years ago.

On the morning of 20 June 1940, the German Naval headquarters in Western France received two messages from Berlin.

The first stated: "In order to protect the local sea area, it is necessary to destroy the cable communication from the British Channel Islands to England. Ask permission for motor torpedo boats and minesweepers to support this raid by the Naval Assault Group."

The second message read: "Occupation of the British Channel Islands is urgent and important. Carry out local reconnaissance and execution thereof. Written orders will follow."

These orders to attack and ultimately occupy the Channel Islands had the code name, Operation Green Arrow and would involve several army and navy assault teams, supported by aircraft cover.

However, before this operation could be launched, the Germans needed to know what type of defences and garrison strength they would be facing in such an attack.

The Germans had known of the existence of the Channel Islands, as their main source of information had been gathered by a German agent who had travelled to Guernsey in July 1938 and reported seeing forts which appeared old and obsolete, which meant this information was out of date and new information would be required.

Pictured: German aerial photograph of Jersey airport. (K. Dietrich)

A series of reconnaissance flights were subsequently undertaken, but the photographs from these missions had been taken at high level and were difficult to interpret and inconclusive, resulting in them being incorrectly described in a report which said: "There are numerous harbour and coastal fortifications and in the harbour area long columns of lorries which could point to the presence of troops."

On Thursday 27 June 1940, two more reconnaissance flights were made over the Channel Islands, with the aircraft crews reporting they had flown at 200 meters and had encountered no resistance.

The following afternoon at 16:00, one further flight passed over St Helier with the pilot stating he had seen two transport ships in the harbour and approximately one hundred and fifty vehicles in the nearby vicinity.

After having received all this new information, the German Command were still unclear whether the Channel Islands were defended, and therefore were unsure what size attack force was required to take the islands, so they decided the only way to determine what defences they would face, was to test them.

Pictured: Some of the shrapnel damage at a house on Commercial buildings. (Colin Isherwood)

In the early evening of Friday 28June 1940, six Heinkel bombers took off from their base at Villacoublay, south of Paris.

Their mission was to conduct an ‘armed’ reconnaissance mission and at 18:45, they had arrived over the Channel Islands.

Three aircraft attacked Guernsey, whilst the remaining three dropped bombs at La Rocque and moments later, Fort Regent, South Hill, Commercial Buildings and the harbour.

Over one hundred and eighty bombs were dropped, with eleven residents in Jersey and thirty-four in Guernsey being killed and over a hundred wounded.

The following day, the bombing raid and invasion plan were discussed again, this time the intention was to send one Infantry Battalion to attack Jersey and Guernsey and an Infantry company to attack Alderney, all supported by arial cover.

This was despite the BBC announcing the Channel Islands had been demilitarised earlier in the day.

However, events quickly changed as in the late afternoon of Sunday 30June 1940, the German Command received news that Hauptmann Liebe-Pieteritz had landed at Guernsey airport, and although he had to depart quickly as three RAF Bristol Blenheim’s appeared, he reported the Channel Islands to be undefended.

Pictured: A white surrender cross was painted in the Royal Square.

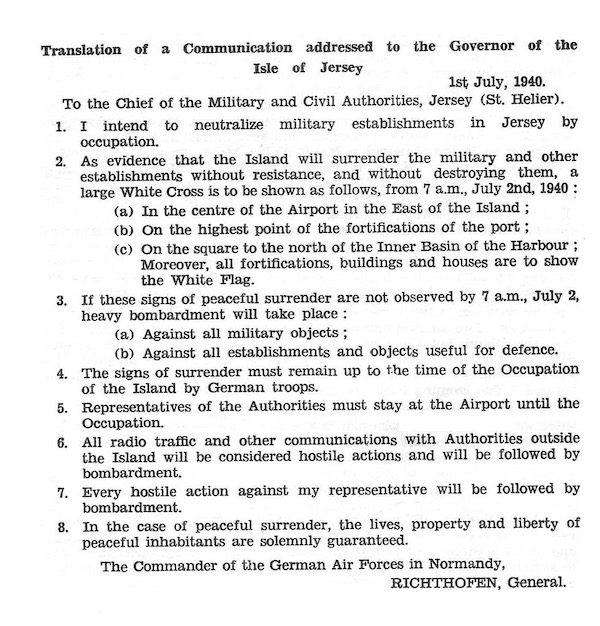

Rather than launching the planned attack, an ultimatum of surrender was issued in the early hours of Monday 1July 1940.

These surrender documents were dropped by parachute from German aircraft and landed at several locations in Jersey: including the Airport, St Aubin’s inner road and outside of St. Marks Church.

Pictured: The ultimatum of surrender dated 1 July 1940.

The ultimatum was addressed to the Military and Civilian Authorities and instructed the authorities to comply with surrender or face further bombardment.

To comply with the surrender, large white crosses had to be painted in conspicuous open spaces and white flags flown from public buildings.

The order had to be completed by early the following day and was signed by General Richthofen, Luftwaffe Commander of Normandy.

At approximately 12:00 on Monday 1July 1940, a lone Dornier Do17 reconnaissance aircraft circled Jersey and after observing a sea of white flags and large white crosses, landed at Jersey Airport.

Pictured: The Bailiff Alexander Coutanche (back to camera), Richard Kern to his right (face to camera), and Von Obernitz (looking left, holding his hands).

The radio operator was Richard Kern, who stepped out of the aircraft making him the first German to arrive in Jersey.

Kern and the pilot, Von Obernitz, reported back that they had seen many white flags and that the Channel Islands had intended to surrender peacefully, meaning no further attacks or armed army and naval assults on the islands were required.

Within a few hours the first German aircraft began to arrive for what was to be five years of occupation.

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.