What would happen if a French nuclear power station went up in flames? What about if a ship transporting radioactive fuel was to hit rocks off Alderney? And how worried should islanders be about radioactive waste dumped in the Channel over 60 years ago?

The first joint review into nuclear risks to the Channel Islands has concluded there continues to be an "extremely low" risk of a radiation incident from nearby nuclear activities.

The report, written by the UK Health Security Agency, reassures islanders that nuclear disaster is unlikely – but sets out steps that could be taken in the unlikely event of one.

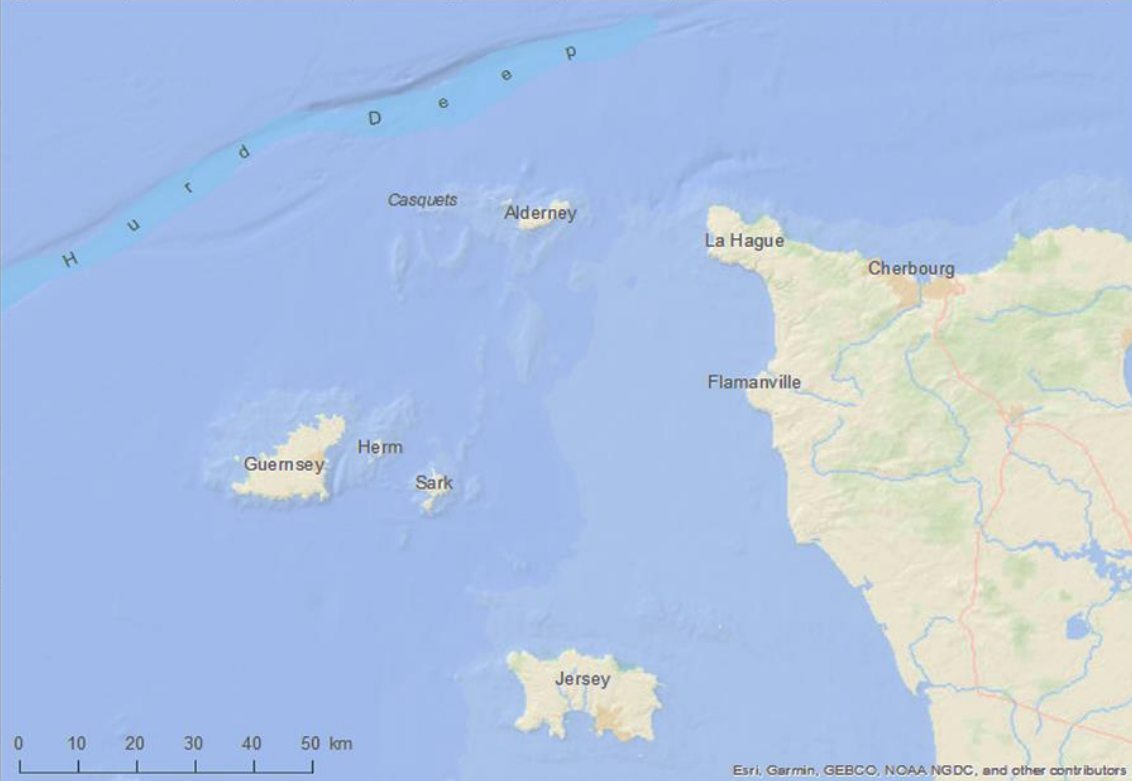

France has three nuclear facilities near the Channel Islands:

a nuclear power station in Flamanville, 18 miles from Alderney, 28 miles from Guernsey, and 22.4 miles from Jersey

a nuclear fuel reprocessing site at La Hague, 12.4 miles from Alderney, 30.4 miles from Guernsey, and 31 miles from Jersey

a naval dockyard in Cherbourg, 23.6 miles from Alderney, 40.4 miles from Guernsey, and 34.2 miles from Jersey.

The UK team modelled what would happen if radioactive material were to be released from these sites.

Pictured: Flamanville, La Hague, and Cherbourg in France all host nuclear materials.

Jersey's Director of Public Health, Professor Peter Bradley said: "They have detailed knowledge of how nuclear reactors work and the years that they were built, and the safety measures, the type of fuel, and so on and so forth.

"It really is important that they have that very detailed knowledge in order to work out the potential risk to health.

"The newer reactors in Flamanville are slightly different, so it's really needed them to be quite accurate."

Researchers focused on the largest nuclear accidents, which are very rare.

They modelled what would happen if a radioactive plume (a cloud of radioactive materials) left one of the nuclear power sites.

Taking into account factors like the wind, researchers found that a radioactive plume could take just one hour to arrive in the Channel Islands.

However, in other circumstances, it could also take four to 12 hours – or even be blown in the opposite direction.

Pictured: Most of France's energy comes from the country's 18 nuclear power plants, giving it one of the largest nuclear programmes in the world.

If a plume was on its way, islanders would most likely be asked to "shelter in place" – going inside buildings, closing doors and windows, and tuning off fans and air conditioning.

They could be asked to stay there for a couple of days, meaning that people could find themselves separated from their families, or be unable to access medical care or assistance.

The report found that iodine tablets – which block the absorption of radioactive iodine by the thyroid gland – are useful and advised that "people should shelter as well as take the tablets".

However, the pan-island Radiation Advisory Group has decided not to stockpile stable iodine in the Channel Islands.

The report also found that evacuating people from the Channel Islands would be unrealistic, and that people would need "advice" on what to eat or drink as any food that is unsealed or not yet harvested could be contaminated.

Nevertheless, they said, at least half of the plumes modelled either did not pass over the Channel Islands at all or had very low radiation levels.

Prompt information from France will be essential if anything goes wrong in their nearby nuclear facilities, according to the report.

The earlier that Channel Island authorities are warned of an issue, the more time they will have to issue a shelter-in-place order.

Although there have been meetings with French authorities – with visits in 2020, 2023, and another one in the works – not all of the necessary information is currently available.

The report notes: "Nuclear accidents are fortunately very rare, and so it is difficult to work out how likely they are.

"The French authorities will have investigated this for their nuclear sites, but this information is not available to the public, to UKHSA or to the Channel Island authorities."

When asked about this, Professor Bradley said: "I think we had a very positive conversation with the French authorities and the préfet [the head of the civil service] in Normandy.

"I think they understand the importance of communication to us.

"I think it's really important that we manage these relationships over time, but really, it's essential, obviously, that we get to know about any incident very quickly.

"And we did receive assurances that that would be the case."

Some of the nuclear fuel used in France is imported via Cherbourg on heavily-regulated, fire-resistant and damage-resistant ships, the report explained.

The UKHSA modelled what would happen if a ship carrying nuclear fuel was wrecked at Les Casquets, just outside Alderney.

"The fuel casks are scattered over the seabed, a small fraction of their contents begin to leak into the environment, but the casks are recovered a year later," the researchers wrote.

With computer models, they found that the leaked materials would end up in the sea and that most people wouldn't be affected – but that there would be a temporary ban on seafood.

Those who might continue to eat local seafood daily would be the worst-affected, the report adds.

"The UKHSA have a knowledge of vessels and the nuclear components that are associated to those," said Professor Bradley.

"They can work out what types of radiation are likely to be ever released, even in the worst-case scenarios."

There is one place near the Channel Islands where radioactive waste is already decomposing, and has done so since it was dumped there 70 years ago.

The International Atomic Energy Agency found that 15,000 tonnes of radioactive waste were dumped in the Hurd Deep – a 590ft-deep trench north of the Channel Islands – between 1950 and 1962.

This waste was left in steel drums, which are now starting to degrade, and monitoring is regularly carried out.

So far, the impact on nearby wildlife has been "of negligible radiological significance", according to the report.

Professor Bradley said the UK experts had again been in a good position to evaluate the risks to the islands, using their knowledge of the specific materials that are deep in the sea and their potential impact on people's health.

Notably, the report revealed that Jersey and Guernsey won't be stockpiling stable iodine, as the Radiation Advisory Group for Jersey and Guernsey unanimously voted against the measure.

Residents of the areas near nuclear power stations in France receive stable iodine tablets every few years. The last round was distributed in 2019-2020 and a new round is in the works.

If they are taken just before a person encounters radioactive particles, they can help prevent thyroid cancer.

Pictured: Director of Public Health Peter Bradley.

Professor Bradley explained why the Radiation Advisory Group for Jersey and Guernsey voted against stockpiling iodine tablets in the Channel Islands.

He said: "We try to evaluate the risks and benefits, and there is a definite benefit in advising people to shelter.

"We considered in detail the numbers on iodine. It has a very limited range of benefits because it only works if there were to be an event in Flamanville."

He added that iodine would only help in a very specific situation, and that its benefits were limited, only protecting younger members of the population and preventing only thyroid cancer.

In addition, tablets of stable iodine have a shelf life, said Professor Bradley.

"As we began to work through all the limitations, we concluded that there was very little benefit" in iodine, he said – but added that "there was a possibility that this could offer false reassurance to people".

Professor Bradley said the report was "needed", with the latest full update dating back to 2007.

He concluded: "We have a plan in place already to manage any incident. That's important.

"The findings from this report confirm that risk is extremely small, but we now know with certainty, because we have the science, that the recommendations we're putting forward are the right ones for the island."

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.